Thursday, March 27, 2008

Saccadic Eye Movements

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Where Do We Get Off

Where do we get off. When did medical students start thinking that they run the show? Has disrespectful behavior always been a problem at schools of graduate education? Is it because we all have a bachelor's degree in something and we think that qualifies us to complain nonstop?

Where do we get off. When did medical students start thinking that they run the show? Has disrespectful behavior always been a problem at schools of graduate education? Is it because we all have a bachelor's degree in something and we think that qualifies us to complain nonstop?One of the most disturbing trends that I have witnessed while at medical school is the drastic increase in the amount of complaining and improper conduct towards professors. During the class time, a student once raised his hand to ask a professor a question, here's how it went:

Student: Doesn't that enzyme do the opposite in the presence of insulin

Professor: Well, I don't think that is correct

Student: No, that is correct

Since when is this considered acceptable behavior? Since when have we decided that that is appropriate for future professionals?

I think it goes back to how many in my generation were raised. A lot of people have mentioned that our generation was the first "you can do anything!" generation. What I mean by that is that most of my generation had parents that told them they could do anything. Never mind that they have no singing ability, you are the worst parent in the world if you don't make them feel like they are the next Pavaratti.

I've always thought my parents did it well. When I was a kid, I wanted to play professional basketball. Rather than just say, "Sure you will someday, you can do anything you set your mind to," he was very pragmatic about it. He said things like, "If that is something that you want to do, than you will have to make big sacrifices to get better at the sport." And I did, for awhile--but then my friends wanted to play with GI Joes, or there was a new movie out at the theater, and I gradually realized that professional basketball wasn't in my future.

I think the best thing that parents can do is encourage their children that many things in life are attainable through hard work, but without having certain innante physical or mental gifts, not everything is possible. If I am 4'7" I'm probably not going to play center for the Piston's someday. If I don't have anything resembling a singing voice, I probably won't be a world famous singer. This doesn't mean that I shouldn't work hard, but I should have parents who can see the gifts that I have and steer me in the right direction.

Another reason that I think that there is so much trouble with respect and discipline is the Political Correctness wave of the 90s-2000s. Don't get me wrong, there are aspects of PC that seem reasonable, such as eliminating the terminology of phrases such as "you people," e.g. "you people are all the same... But one of the downsides of the PC movement is the idea that there is nothing that is right or wrong.

Heaven forbid a teacher uses red ink to grade a paper! Who knows what might result from that! The child's fragile psyche could be forever damaged as a result from the 70% that they got on a test. It's pure ridiculousness and I think that it has contributed to the mentality that many of my peers have that they are always right. Not to mention the fact that they are probably angered that medical school grades are on a strict curve, and that 2/3rds of the students don't get scores above 90% anymore.

In summary, it's very frustrating to be surrounded with so many smart yet rude medical students, especially when the few obnoxiously vocal will be thought of as representative of the entire class.

Monday, March 24, 2008

Top Ten Pistons Buzzer Beaters

Here's one by Rasheed

The Allure of the Mountains

water, people seem to have an almost magnetic draw to living at higher elevations (or at least near them). So sacrificing the rich, sea-level air millions of people either hike, climb or live among the mountains.

water, people seem to have an almost magnetic draw to living at higher elevations (or at least near them). So sacrificing the rich, sea-level air millions of people either hike, climb or live among the mountains. To me the mountains represent the unknown. Every step upward is a step into a world that very few get to experience. A world of mountain meadows, evergreen forests, and snow capped peaks. The time I've spent in the mountains has been an opportunity to spend a day in another world. In an age of urban sprawl and suburban developments, mountains represent one of the last natural frontiers onto which the spoiling hands of humanity haven't yet reached.

To me the mountains represent the unknown. Every step upward is a step into a world that very few get to experience. A world of mountain meadows, evergreen forests, and snow capped peaks. The time I've spent in the mountains has been an opportunity to spend a day in another world. In an age of urban sprawl and suburban developments, mountains represent one of the last natural frontiers onto which the spoiling hands of humanity haven't yet reached. pain in your legs with mental toughness. They allow you an unparelled test of endurance, as many climbs last hours to days.

pain in your legs with mental toughness. They allow you an unparelled test of endurance, as many climbs last hours to days. Friday, March 21, 2008

Simple NCAA Tournament Picking Rules

1. Always choose the #1 Seeds in the first 2 rounds, almost always in the third round.

1a. The following rules should be disregarded in the final four. Then you are on your own.

2. Never pick a team whose name is "X State" unless it is Michigan State (Kansas St. got me this year, but it almost always holds true).

3. Never pick the underdog that everyone else is picking--George Mason proved this point.

4. Pick the Big Ten teams to beat any other team not in the ACC--even then think about picking the Big Ten team. See point 14 for a clarification.

5. Pick West Virginia to win unless they are seeded worse than 11.

6. Pick Syracuse to win at least two games any time they make the tournament.

7. Don't pick teams that got in because they have done well in the past, e.g. Arizona (I almost pick AZ because of Kevin O'Neill--the former Detroit Piston's assistant, but luckily I realized that would have almost violated rule 15).

8. Pick any team with the word "Texas" in it until you would be forced to violate one of the other rules.

9. Never pick 16 seeds over 1 seeds or 15's over 2's, nice try though Belmont.

10. If all else fails pick teams that you want to root for, it will at least make the games more interesting.

11. If you are going to pick a big upset, pick a team that is "hot" coming into the tournament. If George had beaten Xavier like it looked like they would, that would have shown this to be true.

12. Never pick Duke to go far if they are a 2-6 seed. For that matter, ACC teams that get seeds between 2-6 don't usually do that well.

13. Michigan State will either be eliminated in the first round or make it to the final four, in most years.

14. Never pick low seeded Big Ten teams, the probably suck and only got in because of the "strength of the conference."

15. Don't pick a team that lost its coach midseason. This could be called the Indiana 08 rule.

16. Never pick against a Tom Izzo disciple (this is one of my Cardinal rules). This applies to Tom Crean at Marquette and wherever Kelvin Sampson ends up. I never picked against Oklahoma when Sampson was there and I wouldn't have picked against Sampson at Indiana. In the case of a head to head pick Izzo over Crean and Crean over Sampson.

16. Never pick against a Tom Izzo disciple (this is one of my Cardinal rules). This applies to Tom Crean at Marquette and wherever Kelvin Sampson ends up. I never picked against Oklahoma when Sampson was there and I wouldn't have picked against Sampson at Indiana. In the case of a head to head pick Izzo over Crean and Crean over Sampson.Wednesday, March 19, 2008

Why Medical School is Awesome (Opening Black Boxes)

The same is true for our bodies. Which isn't to say that the average person is completely ignorant of biomechanical processes, I've known since high school biology that when one puts their hand on a hot stove a reflex arc is triggered that causes you to quickly remove your hand before you are even consciously "aware" of it. But with that level of knowledge, you sometimes don't even know what you don't know.

But one of the best aspects of medical school is that you are constantly confronted with aspects of medicine that most of the world views as a black box. For instance, the subject matter for today was the anatomical basis for pain. To me, pain has always been more of an idea than something concrete. Pain is what happens when you try to open a package with a sharp knife and it slips and cuts into your finger. But in medical school you get the opportunity to dive deeper.

You can understand the basis for why you rub your arm after bumping it on the table. You can understand why people with spinal cord damage have very little return of functionality below the damage, but even better you have a whole new set of deeper questions you can explore.

Somewhere within the difficulty of medical school are the things that keep us coming back, things like opening up black boxes.

An Out of Context Quote

-My Pastor

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

The Free Clinic (The Importance of Speaking a Patient's Language)

Yesterday at the Clinic that I volunteer at periodically there was a man who came in who is a missionary to Detroit. Yes, that's right he has been sent from his home country of Venezuela to be a missionary to the Spanish speaking population of Southeastern Michigan--perhaps a sad commentary on the work that the local churches were doing to minister to those of the inner city.

So I went out into the waiting room and called Mr. Hernandez back into one of the rooms of the clinic. As we were walking, I asked him if he spoke any English, to which he responded in the negative.

I did my best to stumble through some of the basic spanish that I still remembered from undergrad combined with a few of the medical terms that I had picked up while working at a clinic whose patient population is 50% hispanic. Most of the sentances sounded something like, "Uh...necessito tocar...uh...su......pression." But as is the case most of the time, he was more than happpy to pretend like he understood every word I was saying rather than appear rude.

This guy had really high blood pressure, and I mean really high. 196/120 high, and I noticed from his chart that he had somewhat poorly controlled hyperlipidemia (high levels of "bad" cholesterol etc.). Once I had taken all of his vitals I told him that I would be right back with the "doctor," who is actually a nurse practitioner--but I didn't know how to say "nurse practicioner" in Spanish, and even if I did, I doubt that he would have any idea what the difference was between that and a doctor.

The next time we went back into the room, we brought one of the medical technologists from the clinic who was fluent in both Spanish and English. Here's how it went.

Sandra

"Ask him if he has been taking his medication"

Translator

"Yada yada yada (for the next minute)"

Patient

(Talks to the translator for around 45 secs)

Translator

"He says that he always takes his medication"

Really. That's all that he said in 30 seconds of talking? I take my medication. Tocarlo. It seems like he could have said that in a word or two, what did he use the other 40 seconds to talk about? And what were you saying the whole time? Neither me nor the LPN said anything (and I'm not sure if she even thought about it, but for me it was a bit of a disconcerting experience).

I realized then why the other doctor wanted me to do as much as I could without using a translator--especially when the only translators that we have available have very little background in medicine. A couple more examples:

Later on the translator kept saying that if he came back and talked to the nurse who specializes in diabetes, they could give him a meter for checking his blood sugar. But when the translator repeated the phrase in spanish she said we would give him a machina para pression (basically, a machine for checking his blood pressure).

I really knew that the message wasn't getting across when the translator didn't know the English word "testosterone," when she was explaining what the patient said to her.

So much of the medical interview can hinge on a single word. Did the patient say he checks his blood sugar occasionally or often. Has he had high blood pressure for 5 years or 14 years. What is the nature of the pain in his chest, is it stabbing or is it like someone is sitting on top of him. These difficulties are increased when you get a translator that fancies herself as a doctor and feels that what gets asked during the medical interview is her business.

The best translators that I have seen are those that take one sentance the doctor says in their native tongue and translates it into one sentance in the patients language. When the patient responds, the translator should stop the patient every sentance or so in order to translate back to the doctor. But in a larger sense, this experience has reminded me how important it is to learn as much as I can of Spanish, as it would be one of the most valuable foreign languages to learn as a future doctor in the United States.

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Very Old Posts--Take Three.

| Someone said something that I really should take to heart the other day. At the meeting for pre-med students, I asked what sacrifices the three-doctor panel had to make in med school as well as during their residency, and one of the doctors said something really thoughtful. She said to enjoy the stage of your life you're in. That seemed so true to me because we, as humans, spend so much time wanting to be older when we're young and wanting to be younger when we're old. Not only that, but often times we fall into the trap of thinking that the next stage in life is going to somehow be easier. If I can just get through college then I can start living life and it'll be so much easier... But in reality life really doesn't get any easier. So why not make the most of the life that you're living right now, no matter how bad it may seem. |

Thursday, March 13, 2008

Second Thoughts on Information Sharing

I received an email informing me of a new program that is just beginning this summer for students in between their first and second years of medical school. As far as I know, this email only went to me, and only because I had applied for a similar program that they decided to discontinue. At the bottom of the email they asked if I might be able to spread the word as they wanted to have 9-10 students take part in the externship this summer.

So what did I do. Without even thinking twice I put together an email that made this program sound like it was the best internship ever, and sent it out to the entire class. For a moment I thought about not sending out the email because the more people that applied, the more competetion I would face, but a second later I decided to send it out anyway. I guess it just goes to show you that someone can support healthy academic competition while still believing that competition doesn't have to extend to all parts of life.

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

Information Sharing in a School With Relative Grades

I'd like to think of myself as a pretty friendly, open person.

In the past I have played on team sports, I would hope that those people on my team would say that I am a "team player."

But if I knew of a website that I thought could help students to do better on a test, I would in no way feel morally bound to inform my entire class via an email.

First, for the unindoctrinated, this is what I mean when I say relative grades. The basis for grading in medical school is done by standardizing how you did on a test with how everyone else did. Therefore if you scored lower than average on one test, your standardized score would reflect that--even if your raw score was 98 out of 100 possible, if everyone else got 99% you would have an unimpressive looking relative score. In the opposite scenario, if the average score on a test was 50% and you got a score of 65% correct, you would probably honor.

ALL medical schools must quantify how students rank within their class. Before one of the two people who read this write an angry comment, read on. You may say, but my school doesn't have grades. Generally people that say that follow up by saying "all we have is Fail, Pass, and Honors." I've got news for you, when you fill out an application for residency you medical school must provide some way of distinguishing your Pass from the other 100 students, if I'm not mistaken this is given on a scale of 16 with the middle of the bell curve set at 8, and with a 16 representing the top 1% of students or so. Although I have not confirmed this personally, I've heard people say that the only time they are graded is in 3rd and 4th year--I find that hard to believe, but I'll take their word for it.

By way of example (hopefully I'm not belaboring the point), at Wayne State we have a system of Z scores where the average on any given test is set to equal a Z score of 500. For instance, if I scored 75% and the average was 75% then my Z score was 500. If I scored an 85% my score would be near 600 (considered "Honors"). A score of 65% would be on the border of failing. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, you can have a very high raw score and a relatively low Z score (once I scored 92% with a z score of 460).

Getting back to the topic, one of the questions someone told me to ask the interviewer when I interviewed for medical school was, "How competitive are the students at the medical school?" In other words, is there a sense of teamwork at the medical school or is it everyone for themselves. To which, most would answer that there is a sense of comraderie in medical school. And there is. But can there be comraderie among people that are competing. I think that there can be, and I don't buy that competition is a bad thing.

Like it or not, we live in the era of American Idol and banning red pens. Perhaps in a reaction to how they were treated as children, there is a whole generation of parents that thought they should lie to their children about their children's abilities. "Sure Johnny, you can be a professional singer, you've got a great voice!" "Of course you can play in the NBA, who cares that you can't make it in the basket." At the same time we tell our teachers. "Don't use red pen to correct homework--it hurts students feelings." Luckily my parents always told me I could do anything I set my mind to, provided that I had some degree of God-given giftedness (I could practice basketball 'til I was blue in the face, but there isn't much need for undersized guys who can't jump).

I hope that our generation treats our children the way that my parents treated me. So that we don't have shocked children who are told for the first time that they can't sing by American Idol. And who realize that to become a doctor/engineer/teacher, you have to outwork a lot of people and that maybe it takes a C or D to realize that.

I've come to the point where I can admit that having a life is going to cost me getting an "Honors" in medical school--it just isn't worth losing all social interaction in the name of grades. Because of competition, I am driven to study many times when I'd rather relax. Because of competition I am able to set realistic goals. Because of competition we have highly educated doctors. Because of competion, I won't send out a mass email. Now if I can just figure out where to find all the information I want to keep to myself.

“Life doesn't imitate art, it imitates bad television.”

-Woody Allen

Saturday, March 8, 2008

Friday, March 7, 2008

Medical Hierarchy

of medical school, but not everyone is as blissfully ignorant as I was--I've heard many patients immediately ask for the "real doctor" (They must be frequent visitors to the ER).

of medical school, but not everyone is as blissfully ignorant as I was--I've heard many patients immediately ask for the "real doctor" (They must be frequent visitors to the ER).But for those in the medical profession, there are countless points at which you are forced to realize exactly where you are on the totem pole. There are obvious things such as the ability or lack thereof of signing off a note on a patients chart. For medical students this means writing out what you think is a good note, then finding a doctor who will check it and sign at the bottom.

Aside from the more obvious things, there are a litany of lesser things by which people are kept in check. I would argue that whether they are intentional or not, they serve as an important check in keeping one from becoming too full of themselves or feeling that they had "arrived" and no longer needed to study.

One of the more commonly referenced is coat length. For those not indoctrinated, the white coat of a medical student only goes to the waist (if that), while the coat of an actual doctor (resident or attending physician) goes all the way to the knee. But I think that the hierarchy can be much more subtle, and even though it is not always recognized as such, those that step outside of it are punished in just as subtle of ways.

For the gunners, although people may tolerate them to their face, I would be surprised if anyone would go out of their way to help them. Say for instance someone knew of a chance to meet with several higher ups in the surgical world, I don't think that the first thing you would do is call them up to let them know about it. If someone wants to be a gunner to the point that everyone can see they're looking out for number 1, people will consciously or unconsciously punish them for it.

Although I personally can't speak to this, I've heard that the same principles apply to medical students on rotations. Don't make the residents look bad. It seems pretty straightforward, but I guess some people were never properly trained in the social graces. (bunny trail: a lot of people say things like "I just need to get past the basic science and start clinical rotations, then I'll really shine"--we can't all be right can we). I wouldn't have said a word when was at the Morbidity and Mortality conference, I don't care if they pointed at me and asked what my name was, I would have hoped someone else would have answered. Real or imagined, I've got a healthy (I think) fear of being blackballed.

Lastly I think there is an even more subtle component. Next time you are in a room, look at the seating arrangement. Say for instance you are in a room with a chair a couch and hardwood floors. I would venture to say that 9 out of 10 times, the most senior doctor will be in the chair, the three residents will be on the couch, and the medical student will be on the floor.

Thursday, March 6, 2008

Signs You May Be At a Clinic That Reuses Medical Supplies

2. While other health care providers are switching to computerized medical records, this clinic is trying out the whole "no records" thing.

3. Any box that once had

now has

now has

4. The insulin about to be injected is a deep shade of red.

5. You notice from his diploma that your "doctor" actually only has a Ph. D in economics.

6. Patients requiring surgery must bring someone with the same blood type for on site transfusions.

7. Bills can be paid in 10 easy payments of 11.99

8. Upon entering, patients take a number from a deli-style machine.

9. Before the doctor will see you, patients are fill out a questionaire asking, "What did WebMD say you have?"

10. Hand sanitizer is coin operated.

Wednesday, March 5, 2008

Very Old Posts--Take Two

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

Scene 1 The scene opens with our protagonist (yours truly), calmly paddling in his kayak across a serene, sunlit lake. (foreboding music) When all of the sudden the protagonist thinks to himself (zoom in on face) "This kayak seems pretty stable, but you know what they say about kayaks..." (Flashback to mother's warning) "If you were to tip over in the middle of the lake, that would be a nightmare. Nightmare...nightmare...nightmare (fade out and snap back to reality...uhh-ope there goes gravity [bunny trail]) Zoom in on protagonist face again. "I wonder how much it would take to tip this over...I'm sure it would take an awful lot..." Scene 2 Scene opens with our protagonist gently rocking the kayak back and forth. "See it is hard to tip over!" When all of the sudden a trickle of water drips over the side. Quickly the drip of water becomes a stream. And then a torent, engulfing the right half of the kayak. The once proud Old Town kayak is now listing heavily to the right, but she wasn't about to give up without a fight. Lurching back to the left, the kayak struggles against the rushing water with all her might, but it was too late. With a gasp she rolled over, like Rasheed Wallace in the playoffs. Scene 3 (Quick shots of our protagonist swimming next to his disabled kayak, a look of sheer horror on his face) Alone and adrift in the middle of gi-normous Lamberton Lake our protagonist looks around for any sign of help coming. Nothing. He realizes that he must either sink or swim...literally. After a few failed attempts at flipping the kayak over in the middle of the lake, our protagonist realizes that he must swim to shore, all the while pulling his kayak behind him! (fade out with protagonist swimming toward shore) Scene 4 The Earth Shattering Conclusion After laboring for hours, trying to get back to shore, our protagonist finally crawls onto shore. Exhausted and relieved, he kisses the ground, before beginning his long walk back to the docks. Just when it seems he is out of danger, he slips, severly lacerating his right foot, blood jetting upwards. But he's already been through so much that day that he continues on, his resolve only further hardened. When at long last he arrives at home, to a grateful country... (roll credits) The Protagonist.........Myself The Kayak...............Old Town Kayak Burt Reynolds...........As himself a ©stew production |

Cheers for Fears

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

On Greed and Medicine

medical school and residency (supposedly to help their fellow man) and then become an utterly different person after they become full doctors? How does a doctor snap, or have "angel of death" doctors already snapped before medical school, and are simply good actors?

medical school and residency (supposedly to help their fellow man) and then become an utterly different person after they become full doctors? How does a doctor snap, or have "angel of death" doctors already snapped before medical school, and are simply good actors?For those that don't want to spend a lot of time reading about the long and short of it, I'll summarize for you.

Within the past few days a story has broken in Las Vegas that a small practice in the city (Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada) has been reusing syringes in order to save a buck or two. Workers at the clinic reportedly were told by the doctor in charge of the center to reuse supplies and medications in order to save money.

Here's an example: say I come in to have some procedure done that requires intravenous anesthesia. The nurse (or whomever) walks in and begins an IV by sticking a needle into one of my veins. Little do I know, but a few minutes/days/weeks ago, that very same needle was stuck into a patient who came in for HIV. Many years later, I now have been infected with HIV as a result of almost unbelievable choices by people that I have been indoctrinated to trust.

Doctors are consistently ranked as the most respected and trusted of professions. And 99.999% of doctors spend every day earning that trust, but a seemingly increasing number of health professionals are being found out as betrayers of that trust. How will this change medical practice in America. Will patients be less apt to agree to necessary surgical procedures? Will nurses have to remove packaging of medical supplies in from of patients (this wouldn't surprise me if it was required in the near future)?

"We need to let them come up with what exactly is the problem. In the meantime, that place is closed."

I'll tell you what the problem is. Greed mixed with zero care for patients well being. There seems to be a spectrum in medicine, a spectrum that goes deeper than statistics like "patients per hour." On one hand you have doctors who are completely absorbed with the pursuit of money. On the other hand you have doctors who can truly say that they are not at all concerned about their income. To the former, I would ask the question, why not go into business, chances are you could make a lot more than in medicine (bunny trail: I think the answer is a formula: middle class/lower class smart student sees 7 years of work = almost guaranteed 100,000 dollars per year for life)

In truth, I think that most doctors fall somewhere in between. I'm on pace to rack up $160,000 of debt and someday I'm going to have a wife and family to support. It's through taking a reasonable look at finances that I am able to say, yes I can stick this out and someday I can pay off my loans and live very comfortably. Does that make me a selfish person--if I drive a new car every five years and live in a million dollar house while many in the world are starving, I think the answer is yes. How do we keep from sliding down the slippery slope into unmitigated greed and waste? If we could answer that question then maybe we could decrease the frequency of outright malpractice.

African Watering Hole Webcam

Sunday, March 2, 2008

A Tribute to RDK

"Tonight was the best lab ever. I actually understood everything and RDK was on top of his game. He was joking around the entire night, which definitely made it fun. He was like, 'Well if only one student understood the lab tonight then I can be happy... I'm not going to say who that is (points at me).' And I said, 'Oh stop it!' in the most obnoxious voice I could do. To which he laughed, good times."

Guest Writer

Shells whistle overhead. A stray rocket crashes into the balcony of a high rise apartment building. A professor is gunned down in a parking lot by a crazed student. While this may sound like the script from the latest Scorsese film, these were just some of the experiences of one Calvin professor during the Lebanese civil war.

“I got my bachelor’s degree from Calvin in 1965, and then I went to Wisconsin for my graduate work,” said Roger DeKock, professor of chemistry. “But [in the early 1970s] there was a downturn in the chemical industry.”

Forced to work in consecutive post-doctorate programs that took him first to Florida and then to England, professor DeKock was more than ready for a teaching position. “While I was [in England] I got this job offer to go to the American University of Beirut. It was my first job offer, so [my family and I] decided that even though it was further from home, we’d better take this job.”

The first couple of years that DeKock and his family spent in Beirut were relatively calm, but the political climate in Lebanon was about to take a turn for the worse.

“People had been muttering things to me at the university, like, ‘Boy this place (Beirut) is getting to be a powder keg — and it really was a powder keg. From the Palestinians in refugee camps to the way the government was set up, there were so many pressures because of the [tensions between] the Christians, Shiites and Sunnis.

“April 13th, 1975. I still remember the day very well. It was a Sunday; the weather was beautiful; it was spring. I remember hearing late in the day that some fighting had broken out in Beirut.”

News reports would later say that a Palestinian gunman had opened fire on several people leaving a church in a Christian suburb of Beirut. In retaliation, a Christian group detained and then killed 26 Palestinian civilians. The fighting would only intensify.

“From certain parts of the campus you could see [two] high-rise hotels; one was the Holiday Inn and the other one was the Beirut Hilton. Opposing factions took over the hotels, and they started shooting at each other from the tenth story up. I distinctly remember trying to sleep that night and hearing shelling in the distance, and that created a very uneasy feeling — to hear fighting going on when one was trying to sleep.”

As the fighting intensified, DeKock’s need to evacuate his family became increasingly evident. “The airport would close periodically and then we couldn’t possibly leave, but one evening my wife and I were going out to get some food, and we saw an airplane landing. I said to her, ‘we’re going to get you and the two children a ticket and get you out of here.’ They got out of [Beirut] before the worst came.”

The sectarian violence between warring factions almost always resulted in collateral damage. “I heard bullets flying on campus — there would just be stray bullets,” said DeKock.

The apartment complex where DeKock stayed was not any safer. “There was a Lebanese army post right on the Mediterranean about a block from our apartment complex called “Bain Militaire.” The part of town that I lived in was the Muslim side of the city — the Christian side was the East side, and periodically the people running the rockets on the East side would try to take out that officer’s club.

“But they weren’t that good at aiming. If you heard the rockets go over you were safe, because they had overshot and they would probably go into the Mediterranean, but sometimes they would undershoot. We had one that landed on our street. It was at night.

“It was a huge explosion, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, what happened?’ But after everything calmed down, there was no shouting or screaming, so we guessed that nobody got killed or injured. We went out in the morning and looked, [and saw] that the rocket had hit on the sixth story balcony across the street and brought down the balcony on some parked cars down below — those cars were totally pancaked under concrete.

“Another thing that I noticed was that people who were normally unstable would really go off the deep end during times of war. That must have happened to one student, because he came onto campus with a gun — this was the spring of ’76. He came and killed two deans; one was the Dean of Student Affairs and the other was the Dean of Engineering.

“We heard on campus that there was some shooting, so we were told to shut our office door and turn our light off because we didn’t know who this person was shooting at. A few hours later we got the all clear and were told it was safe to leave. I went to walk home, and as I was walking by the School of Engineering, I walked by the pool of blood where the Dean of Engineering had been killed in the parking lot. He had tried to outrun the student.”

The atmosphere in the classrooms took on a different type of tension. “[Students] didn’t start talking politics to each other on campus — they knew not to do that. It’s like here at Calvin, if you know that somebody is a Bush supporter and you’re not, you just decide between each other to keep quiet. I think that there was a lot of disagreement among students but they didn’t start getting into shouting matches.”

The effects of the civil war stretched into other areas of civilian life. “I spent a lot of time just trying to get groceries. Something that would’ve taken me 30 minutes a day here, now could take two hours, waiting in lines to get bread, milk or meat.”

As many expatriates fled war-torn Beirut, anything that could not be taken on a plane was left behind. “Several of the people that we knew had pets, and they all left them behind with me. I didn’t want to just turn them loose, because when people started to leave, they just let their pets run loose in the city, and that was a horrible life [for the animals].

“I ended up with all kinds of propane gas cylinders that you would use for cooking. When people left, [all of their unused cylinders] ended up with me. I had 10 propane gas cylinders, and when I left I passed them on to someone else.”

The roughness of war contrasted the beauty of Beirut at peacetime. “When we lived there [before the civil war] people called Beirut the Paris of the Middle East. Arabs from the gulf countries would all come to Lebanon in the summer because the climate was so moderate.”

Because of the proximity to both the mountains and the Mediterranean, Beirut was once a popular tourist destination. “The mountains were about a 30 minute drive [from the Mediterranean]. People used to say that you could go swimming in the morning and skiing in the afternoon,” said DeKock.

In the summer of ’76, DeKock decided enough was enough. “The university would close periodically, the hotels were burning, the downtown — which was about three miles from where I lived — was destroyed while I was there. I left because it was dangerous, I thought, ‘why not get out while I can?’ I didn’t like being away from my family.”

From the mid-‘70s to the ‘90s the civil war in Lebanon continued in one form or another, and although formal warring has ceased, the area remains a hotbed of political strife, as evidenced by the violence between Hezbollah and Israel this past summer.

Xanga!

Here's a couple of really "old" entries:

Monday, January 30, 2006

I think that the more I experience life, I've found that there are two types of people in the world. Those who are content to consistently run away from their problems and those that choose to stay and try to make the best of the hand they've been dealt. I find that every day I have to fight being the first person.

Note to parents: Your son/daughter is no more/less unique because his name is spelled Jaymes or James, also this goes out to all the people who've named their daughter Allison, Allyson, Alison, or however else you can think of spelling it; you aren't doing anyone a favor, just creating a thousand headaches for your son/daughter because no matter how many times your child tells someone, it's always going to be spelled Jason and Allison. Also if your last name is Williams, don't name your son Jason, I think that there are about 1 billion Jason Williams' in the world already. Just to give you an example Jason Williams (NBA players) 1. played for the New Jersey Nets then killed his limo driver (2) Played for Duke and the Bulls until he took a tree on in his motorcyle and destroyed both of his legs and (3) got traded to the Heat from the Mephis Grizzlies. Oh and there's a Jason Williams who plays for the Michigan State football team and also one that scored 3 goals in 16 minutes for the Red Wings. And that's just the first ones that come to mind...

Here's a conversation with my dad (on AIM):

stewb1943: Si Senor

baptistsoccer: haha

baptistsoccer: si means if

baptistsoccer : sí means yes

stewb1943 : you're too good, thought I had you there

(later on)baptistsoccer: love ya dad

stewb1943: me too

Sunday, September 25, 2005

Wasn't it great to be ten and the only decision you had to make was whether you wanted to play tag or wiffleball.

People should start doing crazy things right now...because who knows when you'll need to use the insanity defense.

I won't bore you with anymore. Good times. Well, maybe a couple more. (I think I convinced myself I was a comedic writer in bloom--to Steven Colbert: I'm still waiting.)

Wednesday, July 06, 2005

I wonder if anyone has actually "backed that thang up" in response to "you'z a real fine woman"

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

I was at work the other day and we've got a bag of "Fancy Mixed Nuts" that I sell, the thing is, they're mostly just peanuts. Now how is it that a bag of peanuts can be called "fancy." I mean seriously, is there anything less "fancy" than the peanut. We use it to make a butter for goodness sake. You don't go in the cupboard and reach for Pecan Butter, now there's a fancy nut...

Saturday, March 1, 2008

Orthopedics

-I have no idea who first said this, but it's true nonetheless

I came into medical school without having a definite idea of what branch of medicine I wanted to go into, and I can still say that I am not totally sure exactly what I'd like to do. But always in the back of my mind I thought I would go into orthopedics.

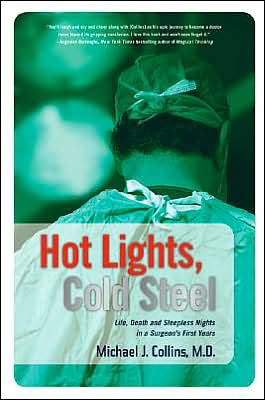

It all started when I read a book entitled Hot Lights, Cold

Steel, written by an orthopedic surgeon named Michael Collins. I think this is one of the best medical-general interest books that I have ever read--an maybe part of it is that I am the type of person that would be interested in orthopedics.

Steel, written by an orthopedic surgeon named Michael Collins. I think this is one of the best medical-general interest books that I have ever read--an maybe part of it is that I am the type of person that would be interested in orthopedics.I played sports in high school (a rather common experience I've read), but I don't think that having played sports is the main reason that I became interested in orthopedics. The reason I feel that way is because if I went into orthopedics and never saw a sports-related patient, I would still consider it to be my first choice.

But when I consider the following reasons, I find it hard to believe that anyone would go into any other specialty, which partially explains why ortho is so popular.

1st (and foremost) Treatment-Effect Relationship: With what little medical knowledge I have, I've realized that I would never want to go into something like internal medicine, where the primary way of caring for a patient is by giving a drug that will fall somewhere on the working-not working spectrum. Orthopedics offers a very definite relationship between the work that you do for the patient (surgical or otherwise) and the results that the patient has, e.g. someone comes in with a broken arm, the orthopedic surgeon reduces the fracture, and a few weeks later the arm is restored to functionality. In orthopedics, problems are can often be completely (or nearly so) fixed, not attenuated to some degree. I've heard a doctor in another branch of medicine joke, "What's a lab test for an orthopedic surgeon? (Pretends to hold vial up to light) Yep, looks blue." Ben Franklin once said that it's better to be thought of as stupid and remain silent, someday I think that I would be perfectly content to be satisfied and thought of as less smart, rather than a miserable neurosurgeon.

2nd Stability through Time: This is one that I've never heard anyone else mention, but it always has stood out to me. I think that 10 years down the road, PAs, nurse practitioners, and supermarket clinics will drastically change the way many specialties will work, esp. family practice doctors (which also is something I considered). But 10 years from now, while the actual techniques and materials that orthopedic surgeons use will have changed, the principles behind the orthopedic treatment of patients will not have changed. Maybe this has some overlap with point one, but what I'm trying to say is this: 10 years ago someone with a bad hip came to an orthopedic surgeon to have it replaced (just like they will 10 years from now). But ten years ago, the treatment for cardiac conditions was largely surgical--now it seems largely medical (from what limited information I've heard). For me this is just another reason to go into a specialty that you can devote your working life to with no fear of having to make big changes somewhere down the road.

3rd Working with My Hands This was never something that consciously led me to consider orthopedics, but rather something that I noticed in hindsight. I enjoy working with my hands--I played baseball in high school, and I have done some woodworking these past two summers and I absolutely love it. Actually, I think it may even go back one level further. I enjoy creating things. I like taking nothing and turning it into something. I like having plywood and 2x4s and turning them into a coffee table. I like in baseball (now softball) that every time the ball is hit to me I have to "create" an out from different circumstances. I like seeing a color that stands out among many different colors and making a photo that I will appreciate for a long time. That's why I think that someday I'll enjoy both the process and the results of orthopedics.

4th Forming Relationships: Perhaps this first part is a biased opinion, it seems that orthopedic surgeons enjoy each others company and that they are generally one of the "happier" doctors that I run into (collectively, I'm sure there are exceptions). The orthopedic practice in my hometown plays as a hockey team in a rec league, and the doctor I shadowed just seemed to be really happy doing what he was doing. Also, I like that there is a component of clinical work in orthopedics. What you are doing isn't strictly surgical and because of this one can take the time to form relationships with his/her patients (although admittedly, there are other specialties which allow for greater relationship-forming). I guess it's the balance that appeals to me. Also, I like that even though orthopedics is demanding time-wise, from what I've heard one can still be a family man/woman--which is very important to me. I got into medicine to help people in a way that is challenging, rewarding, and scientific, not to desert my future wife and use the excuse of a calling. A calling is feeling led towards medicine--so much so that you would spend the prime of your life pouring over books and working through long hours of residency. It's not an excuse to spend 100 hours a week working (post residency) and think that is what's right for your wife/husband and 5 children. So to summarize that mini rant, orthopedics allows one to self limit the time put in so as to have a balanced life.

5th Medical Mission Work (not necessarily ortho-unique): Someday I would like to do medical mission work, and I think that having some surgical skill, be it general orthopedics or otherwise, would allow me to be the most effective at helping the under-served of another country. In other words, having a surgical skill would allow you to perform a greater variety of services to the indigenous population than perhaps an internist would be able to--this is not at all meant to be a knock on other specialties.

6th Condition Diversity Orthopedic surgeons work throughout the body and it seems like it is harder to be pigeon-holed (unless you want to be) than it is in other specialties. Whether it is true or not, I've heard that the majority of the work a general surgeon does is gall bladder removals and appendectomies, and to me at least it seems that orthopedics allows the doctor to decide what they would like to focus on/not focus on.

Cons: Long hours during residency, on the longer end in residency length

This is why I don't know who would want to do anything else, that said, I still have very little practical knowledge about medicine itself and am still open to changing my mind.